“Waka de Atoka”

“Waka de Atoka”

km 7 Ruta A-133

(19 K 369519.00 m E 7952473.00 m N)

Evidencias:

-Geoglifo Llama (AZ-20)

-Construcciones mortuorias (AZ-19)

“Waka of Atoka”

Km 7, Route A-133

(19 K 369519.00 m E 7952473.00 m N)

Evidences:

-Llama geoglyph (AZ-20)

-Mortuaries constructions (AZ-19)

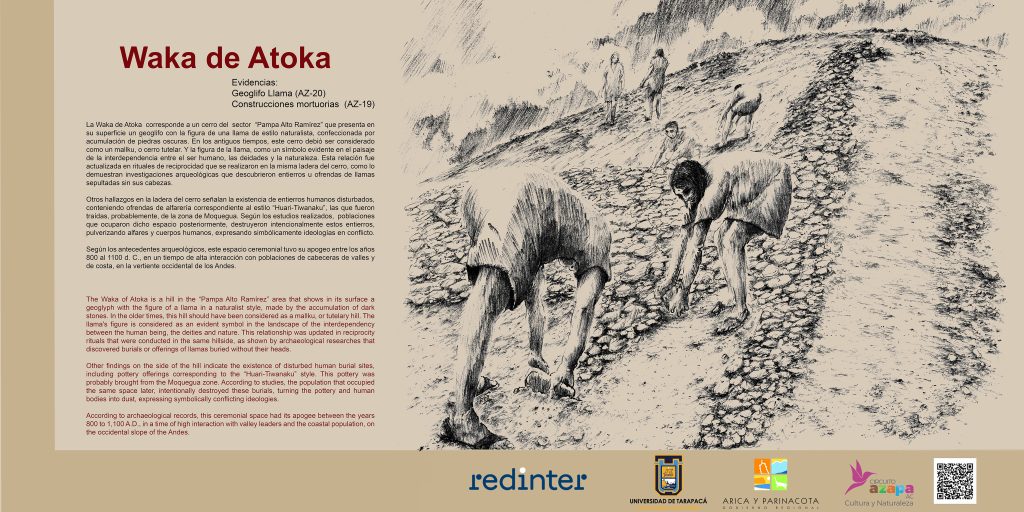

La Waka de Atoka corresponde a un cerro del sector “Pampa Alto Ramírez” que presenta en su superficie un geoglifo con la figura de una llama de estilo naturalista, confeccionada por acumulación de piedras oscuras. En los antiguos tiempos, este cerro debió ser considerado como un mallku, o cerro tutelar. Y la figura de la llama, como un símbolo evidente en el paisaje de la interdependencia entre el ser humano, las deidades y la naturaleza. Esta relación fue actualizada en rituales de reciprocidad que se realizaron en la misma ladera del cerro, como lo demuestran investigaciones arqueológicas que descubrieron entierros u ofrendas de llamas sepultadas sin sus cabezas.

Otros hallazgos en la ladera del cerro señalan la existencia de entierros humanos disturbados, conteniendo ofrendas de alfarería correspondiente al estilo “Huari-Tiwanaku”, las que fueron traídas, probablemente, de la zona de Moquegua. Según los estudios realizados, poblaciones que ocuparon dicho espacio posteriormente, destruyeron intencionalmente estos entierros, pulverizando alfares y cuerpos humanos, expresando simbólicamente ideologías en conflicto.

Según los antecedentes arqueológicos, este espacio ceremonial tuvo su apogeo entre los años 800 al 1100 d. C., en un tiempo de alta interacción con poblaciones de cabeceras de valles y de costa, en la vertiente occidental de los Andes.

The Waka of Atoka is a hill in the “Pampa Alto Ramírez” area that shows in its surface a geoglyph with the figure of a llama in a naturalist style, made by the accumulation of dark stones. In the older times, this hill should have been considered as a mallku, or tutelary hill. The llama’s figure is considered as an evident symbol in the landscape of the interdependency between the human being, the deities and nature. This relationship was updated in reciprocity rituals that were conducted in the same hillside, as shown by archaeological researches that discovered burials or offerings of llamas buried without their heads.

Other findings on the side of the hill indicate the existence of disturbed human burial sites, including pottery offerings corresponding to the “Huari-Tiwanaku” style. This pottery was probably brought from the Moquegua zone. According to studies, the population that occupied the same space later, intentionally destroyed these burials, turning the pottery and human bodies into dust, expressing symbolically conflicting ideologies.

According to archaeological records, this ceremonial space had its apogee between the years 800 to 1,100 A.D., in a time of high interaction with valley leaders and the coastal population, on the occidental slope of the Andes.